Blight on rice: The export ban on non-basmati white rice reveals deeper issues

The Union Government has imposed a ban on the export of non-basmati white rice to ensure its adequate availability in the Indian market and to allay the rise in prices in the domestic market.

By Piyush Aggarwal, Ankita Tiwari, Pathikrit Sanyal: While the internet laughed at videos of Non- Resident Indians (NRIs) thronging supermarkets in the US to buy rice like there was no tomorrow, paddy farmers back at home in India, especially in north Indian states, experienced little amusement.

Renu Singh, a farmer in Jhajjar, Haryana, told India Today: “Last year, we produced about 100 quintals of rice. But this time, excess rain ruined our crop. We still haven’t been able to drain our fields.”

Both situations, Renu’s dismay and the NRIs’ rice anxieties, are tied to a recent directive from the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food & Public Distribution.

The former is the consequence, and the latter is a likely cause. In order to ensure the “adequate availability of non-basmati white rice in the Indian market and to allay the rise in prices in the domestic market,” the Ministry on July 20 amended its export policy from “Free with export duty of 20 per cent” to “Prohibited”.

PRICE RISE

The ministry’s reasoning remained vague. “The domestic prices of rice are on an increasing trend. The retail prices have increased by 11.5 per cent over a year and three per cent over the past month,” it said in its notification, while also adding that non-basmati rice (parboiled rice) and basmati rice formed the bulk of rice exports, whose export policy remained unchanged.

Non-basmati white rice accounts for approximately 25 per cent of India’s total rice exports, which is not insignificant.

India accounts for more than 40 per cent of world rice exports. This was a record 22.2 million tonnes in 2022, which was more than the combined shipments of the world's next four biggest exporters: Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan, and the United States.

And Pakistan’s rice exports have been shrinking. Its exports of rice saw a negative growth of 15.82 per cent in the first seven months of the current fiscal year following the devastation caused by floods in paddy fields in Sindh.

On the sharp increase in rice exports in India, the Ministry of Consumer Affairs pointed to high international prices caused by geo-political scenarios, El Nino sentiments, extreme climatic conditions in other rice-producing countries, “et cetera”.

But high international prices are as much a consequence of such actions as they are a cause.

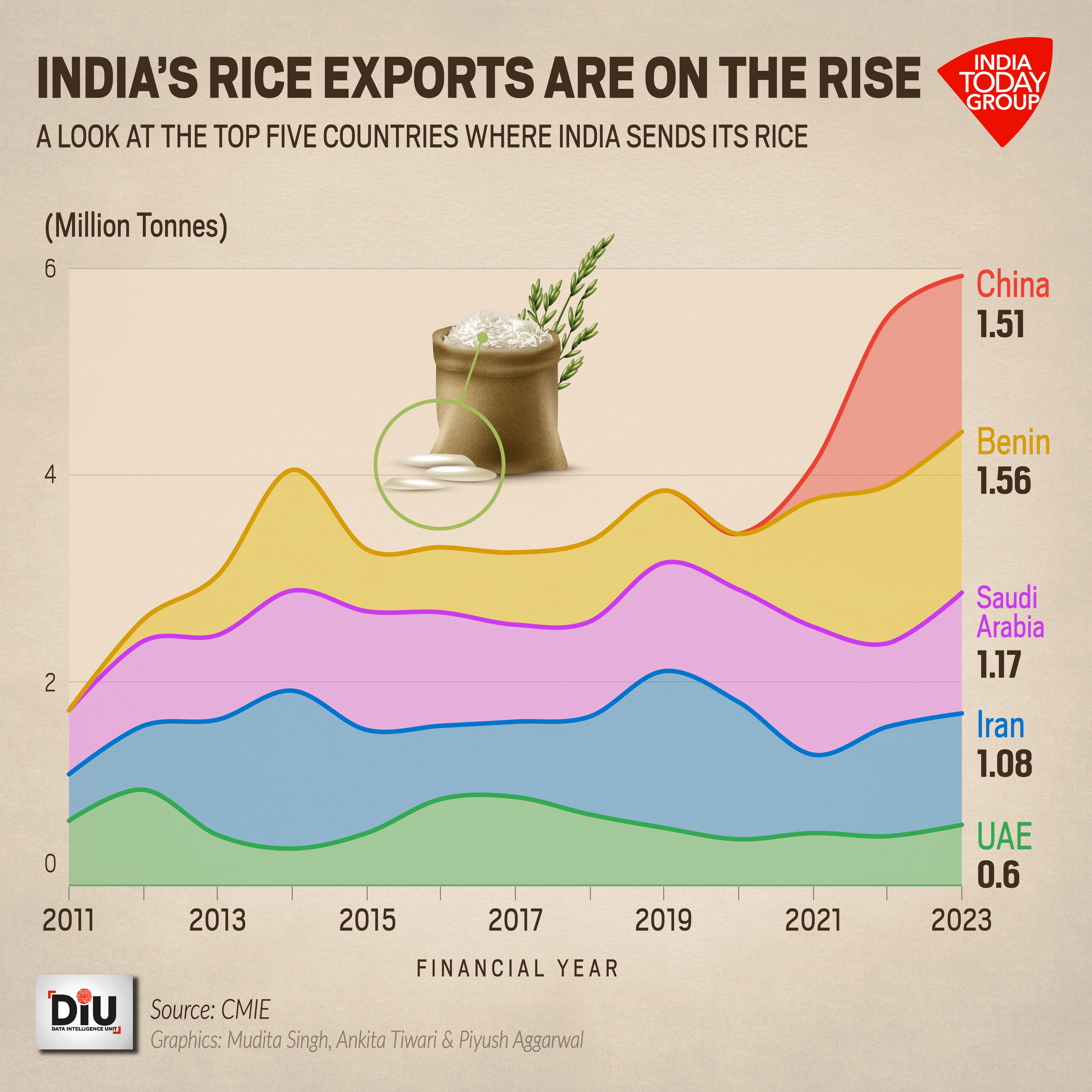

Looking at the country-wise data on rice exports, the top importers are a mix of African and Asian countries, with Benin and China at the top. Interestingly, China, a major global player and the world's largest producer of rice, is also a significant importer of Indian non-basmati rice.

Other Asian countries include Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates.

The Economist noted in a recent report that India’s export ban could disrupt the market further “through contagion.” It cited Vietnam’s 2008 rice exports ban that reportedly prompted India, China, and Cambodia to follow suit. These restrictions, the World Bank estimated, increased global rice prices by 52 per cent.

IN A PADDY

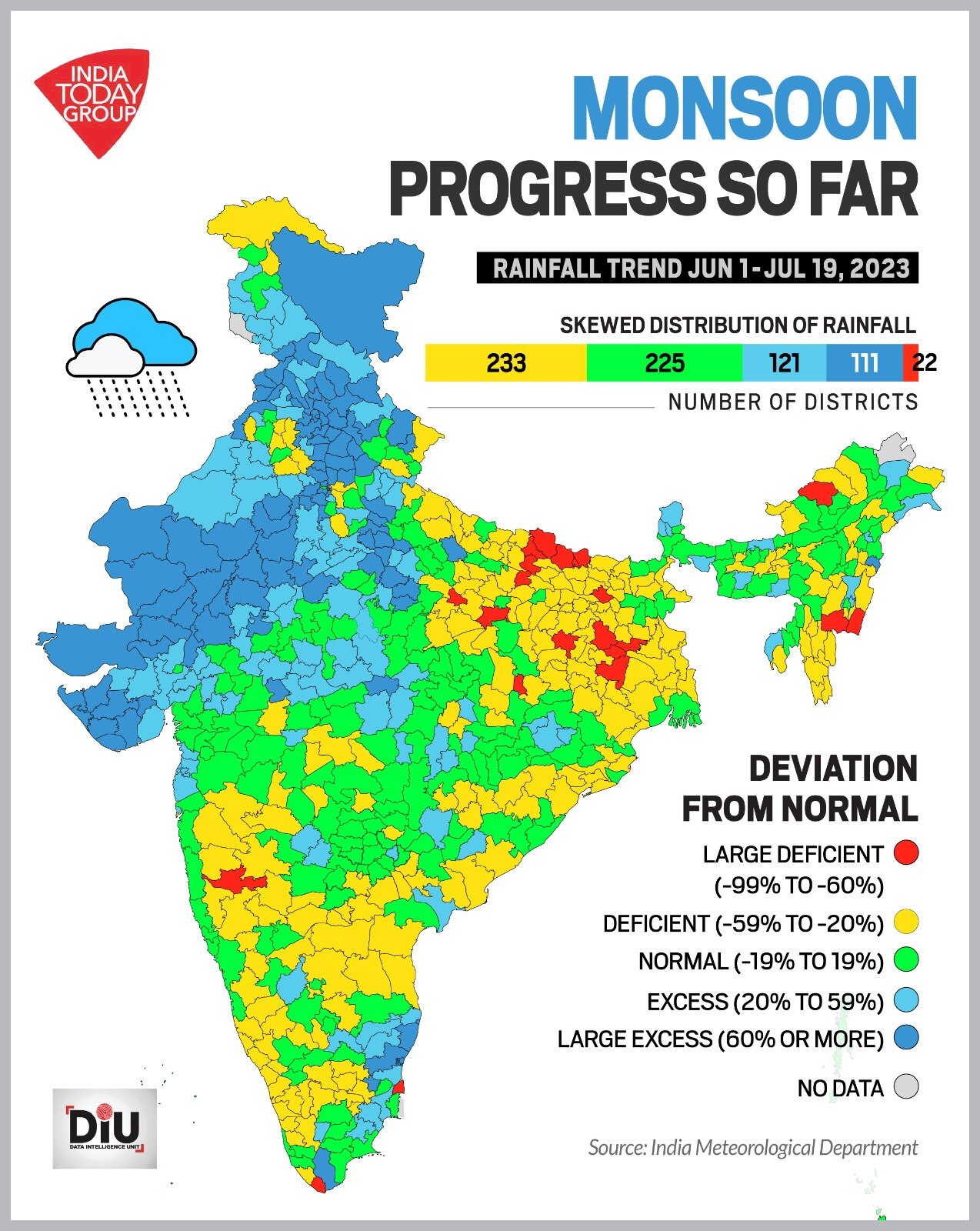

Uneven rains have put rice farmers across India in a difficult spot. While northern and north-western states received excessive rains, southern and eastern regions have so far experienced a deficit. Both spell doom for farmers.

Heavy rainfall in northern states damaged newly planted rice crops. Sonia, a farmer from Sonipat in Haryana, told India Today that her family rented land, spent money on a variety of seeds, and sowed the paddy crop. But excess rain destroyed it all.

“Where we would normally earn Rs 100, this time we may earn just 25 paise,” she lamented, explaining that the crops they planted last week drowned in knee-deep water that they were unable to drain.

In West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh, however, the lack of rain is worrying paddy farmers. “The sowing process is usually done by July 31,” said Ankit Singh of Patna in Bihar, “but we haven’t been able to so far because of the drought.”

He explained that this had been the case in 2022 as well, and rains after August destroyed a lot of the produce. “If it doesn’t rain by August 15, our crop will be ruined.”

A Reuters report noted that delays in planting after mid-July typically result in lower yields in much of India. Weather agencies have also forecast that El Nino could curtail rainfall in August and September. El Nino refers to abnormal warming of surface waters in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, which is known to suppress monsoon rainfall.

SUPPLY AND DEMAND

While India’s rice exports are on the rise, the picture is quite different when it comes to production. Total rice production in the country increased significantly between 2011-12 and 2014-15. However, it decreased thereafter and reached its lowest in 2017-18.

Since then, it has been gradually increasing but has yet to reach the peak production levels of 2014-15.

Similarly, the production of non-basmati rice significantly increased from 2011-12 to 2014-15. However, there was a drastic decrease in production between 2014-15 and 2016-17 and has been unsteady ever since.

Overall, production of all varieties of rice has been on a downward trend since 2014-15, with small periods of recovery in between.